Deserve's got nothing to do with it

Making sense of the senseless

For all the ink that’s been spilled over the recent bloodshed in the Middle East, it’s interesting that no one seems entirely sure what to call it. Indeed, while much of the ink has been dedicated to how unprecedented the initial attacks supposedly were, it seems we have all grown so accustomed to the intractability of the broader conflict that it feels somehow dishonest to suggest some kind of historical progress by distinguishing each new successive phase from the last. Eventually historians will have to settle on something, but for now the matter is the preserve of journalists, who seem content with vague references to a violence that, after all, we all know is taking place.

The upshot of this nominative indeterminism is that those of us lucky enough to relate to this violence solely as spectators have thus far also been spared having to read any articles excoriating this dissonant relationship, inevitably entitled some variation of ‘[The October 2023 Gaza−Israel Conflict]1 Did Not Take Place’. This is no small thing, given that examples of this genre can be found for virtually2 every3 conflict4 of public note going back to the 1991 Gulf War, the non-existence of which was famously remarked upon by the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard. Granted, Baudrillard’s argument was that this ‘war’ was so choreographed, its outcome so inevitable, that it hardly warranted the title5, whereas the defining feature of this recent violence has been how it took everyone by surprise—but then the outcome of this initially surprising outburst has been predictable enough. And in any case, the actual applicability of these arguments has always been somewhat secondary to their reliably attention-grabbing titles6—who wouldn’t be intrigued to learn that something that very clearly did take place, in fact did not? Fortunately, for the moment, it seems there is not enough agreement on what’s actually taking place in Israel for whatever that is to be worth denying.

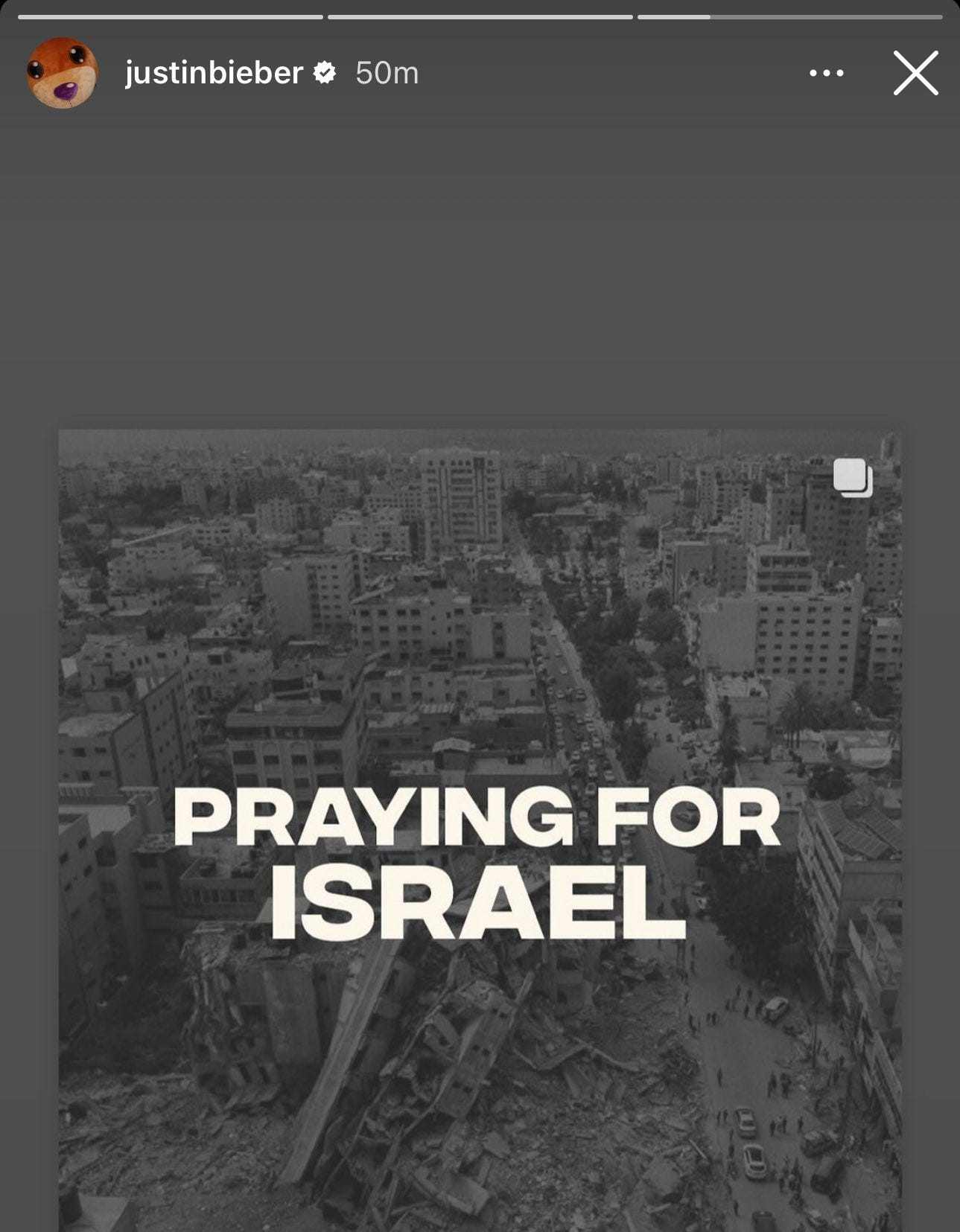

The mercy here is not so much that we viewers at home are spared the discomfort of reckoning with something as complicated as our dissonant relationship with foreign violence, but rather, that we are spared the tedium of reckoning with something that’s by now so passé. This is not to dismiss Baudrillard, who really is just a victim of his own success here; he was clearly on to something when he described the ‘hyperreality’ of western existence, and this is indeed quite evident in our voyeuristic relationship to overseas destruction. But this being the case, it ought to be our prerogative to find the umpteenth variation on this theme a little boring. The [October 2023 Gaza−Israel Conflict] is, in any case, a much more artistically mature conflict than the first Gulf War; more open to interpretation, and more demanding of its audience. In 1991, CNN could only present a single, more or less coherent narrative on a conflict, but the hyper-individualised, algorithmically-targeted media we enjoy today can tailor a different reality to each consumer’s preferences, even when they themselves don’t know what those actually are. These disparate narratives then provide us with endless opportunities to debate and discuss our various realities in order to generate yet more narrative significance, up to and including essays arguing that the thing we’re all arguing about never actually took place. In this new environment, even actual propaganda is subject to the whims and caprices of a marketplace of ideas that has grown so complex it defies any attempt to understand, much less meaningfully manipulate.

We, the audience, are thus stuck with something of a dilemma. Confronted with the essential triviality of our worldviews, mediated as they are by spectacle for no sake other than its own, we have two options. The first is to simply concede our impotence in the face of history. In this context, that essentially means adopting what Sam Kriss recently called a ‘grubby, scummy cynicism’7 which regards the suffering and death we are presently confronted with as simply an historical inevitability, to which any moral response beyond—perhaps—a vague, directionless regret is superfluous. There is, of course, a certain cowardice to this renunciation of moral reasoning, yet seen from this remove, the other—and by far more popular—option is little better. However natural an impulse it may seem, to insist on the legitimacy of one’s emotional investment—be it dedicated to partisan fervour or one’s own internal strife—is in some sense just an assertion of one’s right to the libidinal satisfaction of the spectacle. This collective response to Baudrillard’s critique of our relationship to reality—implicit, but emphatic—essentially amounts to little more than the favourite refrain of the Marvel fan: ‘let people enjoy things’!

This might seem like a fairly damning characterisation of the great majority of people reacting to this conflict, at least some of whom the reader will presumably feel don’t deserve such harsh treatment—but really it needn’t be. One upshot of grubby, scummy cynicism is that it does not oblige one to make that kind of moral judgement any more than it requires a moral judgement on the actual parties to the conflict, which suggests at least the possibility of some kind of synthesis between these two, clearly unsatisfactory but also apparently irreconcilable responses to the dissonance which characterises so much of our reality. To resolve this contradiction, it is necessary to establish how we actually arrive at it. There are at least three levels of abstraction here, each characterised by a contradiction that must be overcome in turn. The first and most obvious is of course the actual, physical conflict itself, which most of the people this essay concerns—which is to say, most of the people reading this—have transcended simply by virtue of not actually being a party to it. Yet still, we are confronted with it at a certain remove, where we are obliged to consider the respective causes and the conduct of each party on a second, more abstract level. Should this prove difficult to parse—as it has for many recently—it is natural to then take a step back and consider a third, yet more abstract juxtaposition between the moral certainty which undergirds both, and a regard for moral ambiguity which might, for instance, derive from seeing abominable acts committed in the name of what one considers a noble cause. But the internal strife which this amounts to cannot be sustained for long; one must eventually either rationalise one’s preference for one of the two causes, or, more productively make peace with the inevitability of such contradictions. This suggests a further level of abstraction, whereupon one arrives at the contradiction we have already established between all of these forms of concrete investment on the one hand, and detached abstraction itself on the other. This, in effect, is what the two possible responses to our collective dissonance with the world actually entail.

To arrive at a level of abstraction where you must confront the nature of abstraction itself must surely seem a little ridiculous, and the reader may well wonder why, exactly, they should care about such an abstract conclusion to what is, after all, an apparently very concrete problem. Consider however, that this abstraction may not actually be an endpoint at all, but rather the starting point from which any serious understanding of anything must proceed. This is essentially Marx’s method in Capital, which he addresses explicitly the Grundrisse. To paraphrase just slightly, adapting his words for our context: simply taking the conflict as it is presented would leave us with a chaotic conception of the whole, and we would then, by means of further determination, move analytically towards ever more simple concepts, from the imagined concrete towards ever thinner abstractions until we had arrived at the simplest determinations (in other words, essentially the process traced above). From here the journey has to be retraced (starting from the most abstract level) until we have finally arrived at the conflict itself again, but this time not as the chaotic conception of a whole, but as a rich totality of many determinations and relations.8

Defining the conflict here in its rich totality is somewhat beyond the scope of this essay, but we can hopefully at least outline the abstract historical moment, from which such a totality might emerge. We have, on at least some level, already started doing so in characterising the conveyances through which our knowledge of the conflict is mediated, and it is apparent how, without an appreciation for this particular relation—that is, the production of subjectivities to no end other than profit—we are left with a chaotic conception of the whole of the conflict, shaped by whatever information a series of algorithms determines is most likely to capture our attention. That it tends to do so by appealing to a sense of morality which it cultivates through this very same process is the crux of the issue.

Regardless of their ultimate valence vis-à-vis the conflict itself—if indeed they have one—these moral impulses which we think are our own, clearly in fact derive from subjectivities which are, if not entirely, then at least substantially overdetermined. This is not to say that moral agency does not exist, but on the contrary that its obvious existence yet equally obvious limitations as an analytical framework are such that it constitutes just the sort of imagined concrete Marx describes. It is an inherently chaotic conception, and this can be seen in the way this moralism serves to obfuscate the far more important, but necessarily abstract question of historical agency, the existence of which is far less clear here. Ultimately, whatever choice the apparent moral agent—be it a man or a ministry—may have pales in comparison to the historical contingencies which frame those choices, and which shape the broad conceptions of morality on which countless other such choices will inevitably be based. Efforts to conscientiously shape these contingencies throughout the era we sometimes call modernity have largely failed, the most substantial of these ending in ignominy around the same time Baudrillard was marvelling at the precision of Raytheon’s GBU-24 family of laser guided munitions9. In the years since, we—at least in the West—have mostly given up trying. In this sense Baudrillard’s observations of the Gulf War are perhaps better understood not to concern the dawning of a new post-modern order, but the death throes of the old modernist one, in which there was still some use for such mass subjectivity-defining spectacles. Yet the market for these spectacles has persisted in the absence of their original reason for being, evolving and developing spectacularly in their scope, but guided in this evolution only by a profit motive no more conscientious than the historical forces it distorts.

Thus the forces of history continue their advance, meandering but irresistible, periodically crushing whomever happens to be in their path. Frequently, these people are Palestinian, sometimes they are Israeli, and overwhelmingly they are probably more or less innocent, but this, really, is merely incidental. Innocence is fine and good of course—it’s something we should all probably aspire to—but it clearly offers no protection from history’s caprices. Yet the historical situation in which those of us who have largely benefitted from these caprices find ourselves tends to continually reproduce a subjectivity that can only perceive the world in these terms. It is both a product of, and the reason for our continued dissonance from the affairs of the world, If we are ever again to at least attempt some conscientious effort to shape society to our will, we must find some way of breaking out of this moralistic framework.

Tom Schueneman

This is the name Wikipedia was using to refer to the conflict when this article was started. At time of publishing, it’s switched to the marginally more evocative ‘2023 Israel–Hamas war’, however the earlier label feels more appropriate in its cumbersome technicality, which promises to secure the conflict only the vaguest place in the popular historical memory, however horrific it may be in the near term.

Biko Agozino, ‘The Iraq war did not take place: sociological implications of a conflict that was neither a just war nor just a war’, International Review of Sociology, 14.1 (March 2004), 73–88 <https://doi.org/10.1080/0390670042000186770

Jarryd Bartle, ‘The war in Ukraine: is it really taking place?’, UnHerd, 1 March 2022 <https://unherd.com/thepost/the-war-in-ukraine-is-it-really-taking-place/> [accessed 11 October 2023].

Hamid Dabashi, ‘The Paris attack did not take place’, Al Jazeera, 27 November 2015 <https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/11/27/the-paris-attacks-did-not-take-place> [accessed 19 October 2023].

Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War did not take place (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995).

Take, for instance, Philip Cunliffe’s recent piece in the New Statesman, regarding the non-existent Ukrainian counter-offensive, the failure of which was likewise never in any doubt—except, clearly, to the media establishment he recriminates for promoting it.

Philip Cunliffe, ‘The postmodern theatre of the Ukrainian counter-offensive’, New Statesman, 25 September 2023 <https://www.newstatesman.com/comment/2023/09/the-postmodern-theatre-of-the-ukrainian-counter-offensive?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Twitter#Echobox=1695629167> [accessed 12 October 2023].

Sam Kriss, ‘But not like this’, Numb at the Lodge | Sam Kriss | Substack, 10 October 2023 <https://samkriss.substack.com/p/but-not-like-this> [accessed 10 October 2023].

Calling this a paraphrasing is perhaps a bit generous; the reader will find that this passage is taken more or less word for word from the introduction to the Grundrisse with only minor alterations to fit the context, and a few clarifying parathenticals.

Karl Marx, Grundrisse, trans. by Martin Nicholaus ([n.p.]: Marxist Internet Archive, 2015), p. xxxiii-xxxv <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/grundrisse.pdf>.

The final collapse of the Soviet Union is usually dated to Christmas Day, 1991; Baudrillard published the final of his three articles concerning the Gulf War in March of that year, however it’s worth fudging the timeline a bit given the apparent symmetry between these two events, which between them mark about as good an end to the modern era as one could ask for.