I fell off a cliff so you didn’t have to

Reflections on pain management

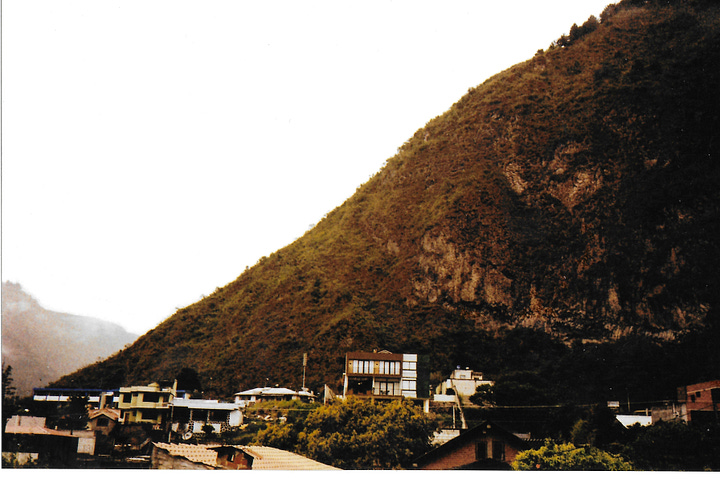

In May 2022, I nearly died. I rolled down a 60-metre cliffside in Baños, Ecuador on a quadbike.

Dear reader, I must exonerate myself: I was not driving the quadbike. I don’t even have a license. I was sitting behind a German girl I had met two days earlier in a hostel. The girl, who I’ll call Belinda, gave every indication of not knowing what the hell she was doing. She fiddled frantically with the gears. I remember feeling a budding dread as we drove off from the quadbike rental with the other eager European tourists and I perceived that Belinda was the only one struggling. Quickly the other bikes sped ahead of us. Ours kept stopping and starting, almost throwing me off the back. I clung very tightly to Belinda’s waist. When we reached our first incline, a fairly inconsequential road two minutes from the rental, I had to force myself to suspend every thought and simply believe, like an evangelical, that we would reach the bottom in one piece.

And we did. And for an instant, I felt good, like a film hero effortlessly dodging bullets. For an instant my fear dissipated.

Things were going smoother when Belinda and I began snaking up the mountain. I looked out at the view. Baños is a stunning place. It sits between two of Ecuador’s ‘regions’: the high, rugged Andes and the lush, explosive Amazon. White strips of waterfall streak down green mountains that rise suddenly from outside the town. The trees have the wild, healthy look of jungle trees. In quick succession mist pours over the roofs like a fleet of ghosts and is then scattered by bright warm sunlight. I pitied Belinda, too busy driving to appreciate the view that sunny morning.

But our honeymoon phase on the quad was sort-lived. Belinda was struggling with the gears again, and whenever we reached a curve our quad would start shaking manically and slip backwards. By now the others were so far ahead that it was completely silent on the road. Eventually, Belinda would tinker with something and the bike would start gliding up again, as if by magic. The thing I felt most uneasy about was the cars, which sometimes came barrelling down the mountain’s sharp corners. We’d been warned to take them wide. At each turn I’d crane my head forward, listening for an engine.

Then on one corner, the quadbike went too wide. It skimmed the cliff’s edge. The wheels on the lefthand side slipped over it, the whole thing suddenly leaned precipitously leftward, and then—these things really do happen in slow motion—we were falling.

Try grabbing the tree on the side of the road—avoid the falling quadbike—a flurry of practical thoughts crowded my head, only to be knocked straight out when I hit the ground the first time. Then I became a mere falling object. Vaguely I registered a series of strong impacts on my body; barely, I perceived the world whirl before me in splotches of blue and green. As suddenly as it began, it ended; and I was lying stomach-down in red dirt.

The aftermath is this: a child spotted us and called his father, who called an ambulance; lucky Belinda avoided most of the fall and, after shedding a few tears over my near-demise, was back in Germany the following week; I was eventually moved in the middle of the night to a hospital in Quito, where I was operated on a fractured spine and smashed knee. I’m basically fine. I was lucky. The orthopaedic surgeons in Europe can barely contain their surprise as they ask whether such a successful operation was really done in Ecuador. Apparently, my knee surgeon exited the operating room after 6.5 hours and declared, ‘I can’t wait till this knee goes back to Europe and the doctors there see what a good job I’ve done!’

*

Unsurprisingly, this has been my most painful experience. In the immediate aftermath of the fall and the operation, the pain in my back was overwhelming, constant, debilitating. Impossible to think. Then the acute period of pain subsided. Now it re-emerges occasionally for an episode or two, which I anxiously fight off with pills and rest.

It has given me the chance to reflect on pain. And I want to suggest the importance of focusing on pain management, rather than pain elimination: the social and transformative elements of pain relief, rather than the medical and numbing ones.

Of course, the line between these two approaches is not fixed, and trying to eliminate pain can be quite wonderful too. I do not rebuff the advantages of contemporary pain medication—just a week ago I eagerly popped a cocktail of pills down my throat to deal with back pain. I only seek to briefly reflect on its limits, and the dangers of over-emphasising it.

You might ask: how could there be an over-emphasis on such a seemingly basic good as pain elimination? For philosopher Byung-Chul Han, ‘a life without pain and fitted with constant happiness will no longer be a human life’ (79) [1]. According to Han, we are losing the ability to narrate and thus metabolise pain as a society, developing instead a tendency to automatically anaesthetise any discomfort or hurt. This tendency, and the concomitant inability to comprehend pain, is a peril to our humanity. Put differently: our humanity requires openness to experience and to the Other, i.e., an engagement with reality. But such openness is inseparable from pain; Han goes so far as to say that ‘experience in the emphatic sense of the term presupposes the negativity of pain’ (53). Han’s concern is that we are gradually creating a ‘palliative society’, one where our lives as engagements with reality are sacrificed out of excessive fear of pain.

The ‘palliative society’ does not only refer to actual pain medication, like the morphine I blissfully received after my accident. Han sees it as a general tendency, both within hospitals and without, to numb discomfort and hurt. It isn’t difficult to think of the myriad ways in which we numb ourselves: alcohol, drugs, social media, Netflix, pills, porn. The admirable panoply of games and media on our phones means we can avoid spending even five minutes alone with our thoughts and the messy, anxiety-inducing, potentially boring real world.

However, sticking with medical pain relief for now, let me reference two varieties.

In the US a powerful pharmaceutical industry inevitably makes medication prominent. My father once had a small operation, in Boston, to remove an outgrowth of skin from his shoulder; they sent him home with two Oxycotins for the pain. He did not even take a Paracetamol. The over-prescription of opioids by American medical professionals is well-documented, and a chief cause of the opioid crisis ravaging the US for the last twenty years [2]. In addition to the specific, harrowing risk of addiction to opioids, there is an expectation, ‘addicting’ in itself: that healthcare should limit pain as much as possible, an attitude-forming prospect that could result in an inability to manage without pain relief, without numbness. Is suffering a couple of days of (not extreme) pain after an operation really so unbearable? In Quito, I looked on with increasing anxiety as the doctors began reducing the dosage of painkiller I received almost immediately after my operation. The body, one doctor told me, can easily adapt to needing things it could previously do without. He was there to remove the oxygen tube I had been comfortably using. Quito sits at 2800m.

The doctors in Quito were not being insensitive, though this can obviously happen. They were attempting to give me only the meds I needed, so I would wean off them sooner. And there was something else in Quito that did, in fact, allow me to tolerate that relative lack of pain medication: people. My room held guests from morning till nightfall, at which point my father would sleep over, curled on a small red couch behind my bed. I even woke up from my operation to the sight of two people chatting over my bed—a friend from Quito and a Dutch acquaintance from a hostel who had brought me my backpack.

Beyond a certain threshold of minimal medication, to which I am heartily grateful, it is not complete numbness but two social acts that, in their simplicity, have stuck with me from my experience of pain and fear: the importance of touch and that of storytelling. Simply holding a hand, stroking someone’s hair, hugging someone, can alleviate suffering. When a member of our group finally found us after our fall, and held my hand, I felt almost a seizure of relief. And when he threatened to let go I cried for the first time. For Adorno ‘the act of being touched by the other’[3] grants us our consciousness, our subjectivity. Han writes with disparagement of the replacement of ‘the curing hand of the Other’ by painkillers: the true experience of being cured, he says, is the experience of ‘being touched and inquired into’ (40, emphasis his). That sincere English expression, being touched by something, relies on the impact another’s touch has: that moment of incredible openness where our more rational processing of the world through eyes and ears cedes to an experience of our bodies, and to the pure possibility incarnated in interaction with the other.

Storytelling is another uniquely human practise that helps us cope and grow stronger. The first night after my operation, though I hadn’t consumed anything in 40 hours, I kept vomiting up a pale sticky substance that resembled glue. My throat ached from the tubes that had been shoved down it. Faced with a long, painful night, my relief at surviving the operation was soon replaced by hopelessness. My father came beside me, grabbed my hand, and began telling me stories. He often does this when one of his children is sick or in pain. He fields around his life for bits of stories that he then extends into eloquent dramas—episodes that on a regular, healthy day, he wouldn’t even mention. In this case it was a romantic drama about two young people he knew. I wanted to tell him that it was futile, nothing could distract me from the overwhelming pain; but then in spite of my misgivings I became interested. It did not send away the pain, not at all, but I was genuinely engaged, making small, fatigued comments on the story’s development. The fact that anything could have shaken me from that awful, deep discomfort was a revelation. For Han, narration is ‘the capacity of the spirit to surpass the contingency of the body. So [Walter] Benjamin’s idea that the story can cure any illness is not so absurd’ (32). The touch gifts one the experience of the body, the story allows one to transcend it; both contextualise and narrate the pain one’s body is giving, inserting it into the broader folds of experience and life.

Simple things—doctors holding my hand on the hospital bed, my parents talking about trivialities—are essential. And they also reveal why the trend toward increasingly atomised individuals unsupported by a community or familial network is worrying, not liberating, and the compensation with anaesthetising distractions and substances unsurprising.

Pain is about the fall I had, or the illness that befalls one, or the ache in one’s bones (and I will not even wander here into the complex thickets of mental pain). But it is also about the social processes we possess, or lack, for managing it. And if the drive towards anaesthetisation ends up cutting us off from those very processes, then we might, I think, do well to question it closely.

Melanie Erspamer

[1] I will cite from the Italian translation of Han’s book (La società senza dolore, Einaudi 2021), with my own translations into English.

[2] For more information, see for instance: here, here, and here.

[3] Aesthetic Theory, p. 331 (Continuum 1997).